.

How Burrowing Owls Lead To Vomiting Anarchists (Or SF’s Housing Crisis Explained)

.

Today, the tech industry is apparently on track to destroy one of the world’s most valuable cultural treasures, San Francisco, by pushing out the diverse people who have helped create it. At least that’s the story you’ve read in hundreds of articles lately.

It doesn’t have to be this way. But everyone who lives in the Bay Area today needs to accept responsibility for making changes where they live so that everyone who wants to be here, can.

The alternative — inaction and self-absorption — very well could create the cynical elite paradise and middle-class dystopia that many fear. I’ve spent time looking into the city’s historical housing and development policies. With the protests escalating again, I am pretty tired of seeing the city’s young and disenfranchised fight each other amid an extreme housing shortage created by 30 to 40 years of NIMBYism (or “Not-In-My-Backyard-ism”) from the old wealth of the city and down from the peninsula suburbs. …

.

1) First off, understand the math of the region. San Francisco has a roughly thirty-five percent homeownership rate. Then 172,000 units of the city’s 376,940 housing units are under rent control. (That’s about 75 percent of the city’s rental stock.)

Homeowners have a strong economic incentive to restrict supply because it supports price appreciation of their own homes. It’s understandable. Many of them have put the bulk of their net worth into their homes and they don’t want to lose that. So they engage in NIMBYism under the name of preservationism or environmentalism, even though denying in-fill development here creates pressures for sprawl elsewhere. They do this through hundreds of politically powerful neighborhood groups throughout San Francisco like the Telegraph Hill Dwellers.

Then the rent-controlled tenants care far more about eviction protections than increasing supply. That’s because their most vulnerable constituents are paying rents that are so far below market-rate, that only an ungodly amount of construction could possibly help them. Plus, that construction wouldn’t happen fast enough — especially for elderly tenants.

So we’re looking at as much as 80 percent of the city that isn’t naturally oriented to add to the housing stock.

Oh, and tech? The industry is about 8 percent of San Francisco’s workforce.

Then if you look at the cities down on the peninsula and in the traditional heart of Silicon Valley, where home-ownership rates are higher, it’s even worse. …

So one contributor to the tech industry’s spread into San Francisco is that the peninsula cities are more than happy to vote for jobs, just not homes.

.

2) Why is the tech industry migrating to cities anyway?

San Francisco’s population hit a trough around 1980, after steadily declining since the 1950s as the city’s socially conservative white and Irish-Catholic population left for the suburbs. Into the vacuum of relatively cheaper rents they left behind, came the misfits, hippies and immigrants that fomented so many of San Francisco’s beautifully weird cultural and sexual revolutions.

But that out-migration reversed around 1980, and the city’s population has been steadily rising for the last 30 years. …

Its rapacious speed may even be accelerating. Witness hyper-gentrification in Brooklyn and Manhattan, or the “Shoreditch-ification” of London. …

The concept of lifetime employment also faded. Today, San Francisco’s younger workers derive their job security not from any single employer but instead from a large network of weak ties that lasts from one company to the next. The density of cities favors this job-hopping behavior more than the relative isolation of suburbia.

There are also some tech industry-specific reasons too. The capital costs required to found a company and launch a minimum viable product are much lower than a decade ago. …

But the big wave of the last decade has been social networking. And every notable consumer web or mobile product of this wave has been seeded through critical mass in the “analog” world. Facebook had university campuses. Snapchat had Southern California high schools. Foursquare had Lower Manhattan. Twitter had San Francisco. These products favor social density. …

As tech workers have moved into cities, the industry has changed San Francisco’s culture and San Francisco has changed the technology industry.

Nevertheless, while tech is fueling San Francisco’s current boom and has helped cut the city’s unemployment rate by about half since 2010, this gentrification wave has been going on for decades longer than the word “dot-com” has existed.

And it’s happening all over the country.

So a great question of our time is how American cities handle this shift. They have to do this in the face of global economic changes that are dividing our workforce into highly-skilled knowledge workers who are disproportionately benefiting from growth and lower-skilled service workers that are not seeing their wages rise at all.

.

3) OK, let’s build more housing!

Wouldn’t that be simple?

But it’s not that easy. While the real estate market is hot, developers are currently building 6,000 units.

To go beyond that, you have to build political will. …

San Francisco’s orientation towards growth control has 50 years of history behind it and more than 80 percent of the city’s housing stock is either owner-occupied or rent controlled. The city’s height limits, its rent control and its formidable permitting process are all products of tenant, environmental and preservationist movements that have arisen and fallen over decades. …

There were struggles in the 1950s and 60s to stop freeways from cutting through the Panhandle and Golden Gate Park, which gave way to another slow growth political movement in the 1970s to push back on downtown high-rises as they encroached into North Beach and Chinatown. In 1986, the city passed a resolution to control the amount of new commercial real estate space that could be built in any single year.

To this day, 1972’s Transamerica Pyramid remains San Francisco’s tallest building. It’s only in 2017 that a taller 1,070-foot tower anchored by Salesforce will open.

As political scientist and longtime San Francisco observer Richard DeLeon puts it:

San Francisco has emerged as a “semi-sovereign city” — a city that imposes as many limits on capital as capital imposes on it. Mislabeled by some detractors as socialist or radical in the Marxist tradition, San Francisco’s progressivism is concerned with consumption more than production, residence more than workplace, meaning more than materialism, community empowerment more than class struggle. Its first priority is not revolution but protection — protection of the city’s environment, architectural heritage, neighborhoods, diversity, and overall quality of life from the radical transformations of turbulent American capitalism.

While we have to thank these movements for preserving so much of the land surrounding San Francisco and the city’s beautiful Victorians, one side effect is that the city has added an average of 1,500 units per year for the last 20 years. Meanwhile, the U.S. Census estimates that the city’s population grew by 32,000 people from 2010 to 2013 alone. …

A coalition of Mission-based non-profits and activists demonstrating against a proposed 351-unit condominium development at 16th and Mission. (From the Plaza16 Coalicion Facebook Page.) …

At face value, this might not make sense. But there are a couple reasons that this happens. One is that gentrification raises the gap between market-rate rents and rent-controlled rents, strengthening the financial incentive for landlords to evict longtime tenants.

Two is that neighborhood organizations representing historically disenfranchised groups have used San Francisco’s byzantine planning process to win concessions from the city’s development elite for the last 30 to 40 years.

Unlike the wealthy waterfront NIMBYists, these communities are at risk of being displaced. If they don’t speak up for themselves, who will? …

In principle, it’s fine to use the levers of urban politics to redistribute the wealth an economic boom creates in San Francisco.

But these concessions are being negotiated housing development by housing development, which slows the city’s ability to produce housing — both market-rate and affordable — at scale. …

The sophistication with which neighborhood groups wield San Francisco’s arcane land-use and zoning regulations for activist purposes is one of the very unique things about the city’s politics.

But the city’s political leadership doesn’t want to change it, because it fears backlash from powerful neighborhood groups, which actually deliver votes.

.

5) Also, parts of the progressive community do not believe in supply and demand.

Yeah, I was surprised by this.

“We can’t build our way to affordability,” is a common refrain. Tim Redmond, who used to edit the San Francisco Bay Guardian, even suggested today that the government should take 60 percent of the city’s housing off the private market over the next 20 years. (I have no idea how you would fund this.)

Several activists also sent me this paper, authored by Calvin Welch, of the Council of Community Housing Organizations.

SF Controller Shows Supply and Demand Does Not Work. …

His organization, the Council of Community Housing Organizations, argues that raw, additional construction will not make housing more affordable to working-class or lower-income San Franciscans. Left to its own devices, the market will only produce housing that chases the very richest buyers. In a time of rising inequality, those market-rate units are increasingly out of reach, even for middle-class San Franciscans. …

His organization, the Council of Community Housing Organizations, argues that raw, additional construction will not make housing more affordable to working-class or lower-income San Franciscans. Left to its own devices, the market will only produce housing that chases the very richest buyers. In a time of rising inequality, those market-rate units are increasingly out of reach, even for middle-class San Franciscans. …

So affordable housing advocates say that developers should be required to have a higher percentage of below-market-rate units built. The issue with inclusionary housing is that construction costs are so high in San Francisco — calculated here to be nearly $500,000 for an 800-foot square unit — that affordable housing requires generous public subsidies.

The Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development says there are 1,759 units of affordable housing that are currently being built or preserved at a cost of $824.5 million. About $274.1 million of that funding is coming from the city, and the remaining $550.3 million has to come from somewhere else.

The federal and state government used to help with this, but their assistance has dropped off dramatically since the 1980s. (Cuts to the federal Housing and Urban Development department budget under the Reagan administration coincided with the rise of urban homelessness in San Francisco.)

When below-market rate units do get built, the lines are massive: 2,800 people applied for the 60 units at this SOMA affordable housing development.

Also, inclusionary housing has its own trade-offs. It can pass on the costs of building below-market-rate units to market-rate buyers, cutting out units that would be affordable to middle-class buyers. Hence, another reason for the disappearance of the San Francisco’s middle-class. …

.

7) Yet we’re arguing over shades of gray. Sorry, supply and demand still totally matter.

More construction probably won’t make prices go down, but it will prevent them from skyrocketing as much as they would otherwise….

The point is that if the entire Bay Area had a more elastic housing supply, it would not only make living affordable for most people, it would allow a far larger portion of the population to find jobs and do things like save or spend money instead of moving somewhere distant and spending their money on driving, or even being unemployed. …

However, it’s hard to have even basic debates over modest increases in the housing supply here because of this ideological dispute.

.

8) 1978 and 1979: Proposition 13 and Rent Control

I keep coming back to the late 1970s because both the city of San Francisco and the state of California made choices that have had enduring impacts on housing to this day. …

Earlier in the summer of 1978, a cantankerous former small-town newspaper publisher named Howard Jarvis led a “taxpayer revolt” as property prices were soaring, threatening to throw home owners out of their homes because of rising tax bills. Jarvis’ idea was to cap property taxes at 1 percent of their assessed value and to prevent them from rising by more than 2 percent each year until the property was sold again and its taxes were reset at a new market value.

.

.

One argument that Jarvis used to rally tenant support for Proposition 13, was that he promised that landlords would pass on their tax savings to renters.

They didn’t. They pocketed the savings for themselves.

Tenants were furious, and rent control movements erupted in at least a dozen cities throughout California, from Berkeley to Santa Monica. …

Without the ability to rely as heavily on property taxes, city governments throughout the state had to favor office and retail development over housing in order to boost sales taxes. It may have even accelerated the homogeny of suburbs as smaller city governments had to cut deals to attract “big box” retailers to boost sales tax revenue, crowding out independently-run stores.

It also created a lock-in effect as California property values soared, creating a bigger gap in property taxes on newly-sold properties and ones that homeowners had held onto for a long time. That rigidity further enhanced the political power that NIMBY-ist homeowners accumulated in suburban city councils throughout the state. …

Because both Proposition 13 and rent control insulate homeowners and rent-controlled tenants from dramatic tax or rent increases when the market undersupplies housing, they undermined political will for building homes. Both of these policies were enacted just as the “Great Inversion” started.

.

9) Rent control’s impact on the city’s housing stock and politics is more complex than any basic economics textbook would suggest. …

Yes, rent control is a blunt instrument of income re-distribution in an increasingly unequal world. It is not means-tested, meaning anyone from well-salaried, white-collar workers to very low-income residents can benefit from it. It also forces a number of small-time, mom-and-pop landlords to individually subsidize someone else’s cost of living in the city. …

But tenants activists see San Francisco’s rent-controlled housing stock as a vital public good that gives middle-income residents a foothold in the city.

And while the make-up of the city’s rent-controlled hasn’t been studied in more than a decade, it likely contains less-wealthy San Franciscans on average than the market-rate units do. In studies of other cities where rent control unexpectedly ended via a change in state law like Cambridge, Massachusetts, tenants in these apartments had lower incomes than those of market-rate renters.

San Francisco’s version of rent control also does not apply to buildings constructed after 1979, so it shouldn’t dis-incentivize developers from producing new units.

Instead, a lot of other factors are constricting supply. That said, I do think it undermines the political will that would otherwise exist for building more housing.

.

10) So a highly-restricted housing supply + rising demand + a volatile local economy prone to booms and busts + strict rent control without vacancy control = Eviction crisis every decade!

San Francisco’s version of rent control lacks vacancy controls, which means landlords can re-set rents at whatever the market will bear when new rent-controlled tenants move in.

The logic is that with vacancy controls, landlords won’t invest in maintaining their properties. But the flipside is that the landlord also has a strong financial incentive to evict longstanding tenants who are paying below-market rates.

So every decade during a boom, there is a tragic, elderly face for the story of displacement. …

.

12) Fuck, this is complicated. Anti-tech sentiment becomes a catalyst.

Tenants-rights activists had struggled to generate momentum for protections against Ellis Act evictions, but villains like real-estate speculators are too nebulous. Indeed, many of the landlords responsible for the bulk of Ellis Act evictions hide behind strangely-named entities like ‘Pineapple Boy LLC.’

Tenants-rights activists had struggled to generate momentum for protections against Ellis Act evictions, but villains like real-estate speculators are too nebulous. Indeed, many of the landlords responsible for the bulk of Ellis Act evictions hide behind strangely-named entities like ‘Pineapple Boy LLC.’

But the Google Bus protests worked.

They were a media sensation.

They tapped into this inchoate sense of frustration around everything from rising income inequality to privacy to surveillance to the environmental impact of the hardware we buy to a dubious sense that today’s leading technology companies aren’t living up to their missions of not being evil.

“The we-hate-tech-workers is mostly a media narrative,” said organizer Fred Sherburn-Zimmer. “It’s not about that. It’s about income disparity. It’s about speculators using high-income workers to displace communities.” …

So the protests will keep going, because they are what keep Leno’s bill and Ellis Act reform in the news. (Don’t take it too personally. You can blame us — the media — for finding protests against globally-recognized brands like Google much sexier than protests against individual Mountain View city council members.) …

.

15) What is the city government doing?

If you can see any possible silver lining in being antagonized every day in protests, it’s that the city government will be really, really, really focused on housing.

A lot of things that weren’t considered politically possible for years are happening now.

- The Board of Supervisors was able to pass a bill to legalize in-law units, which can be anything from garages to attics that have illegally housed tens of thousands of San Franciscans for decades in a shadow housing market.

- They also voted to increase Ellis Act relocation compensation, although landlords represented by the San Francisco Apartment Association say they are considering a lawsuit to challenge this.

- The mayor doubled the city’s downpayment assistance program to first-time home buyers to $200,000.

- The mayor pledged to build or rehabilitate 30,000 units in the next six years, with one-third of those being permanently affordable to lower and moderate-income families.

- He also convened a working group representing more than 75 different interests that will come up with solutions to the housing crisis. You can read different ideas for solving the housing crisis here from SPUR, the San Francisco Housing Action Coalition or the Council of Community Housing Organizations. There is no silver bullet in any of these. It’s a hard problem.

- Lee, Leno and others are collaborating on this Ellis Act bill in the state legislature.

- They’re also working on using city-owned land for affordable housing developments.

- Ahead of all these protests, Lee also got voters to pass an Affordable Housing Trust Fund back in 2012. But any projects from it are also likely to be mired in that crazy planning process. …

.

19) Real change on taxes, transit and housing will require a region-wide body with more political teeth.

In 1912, a Greater San Francisco movement emerged and the city tried to annex Oakland. Understandably, Oakland refused.

For more than a century, the Bay Area’s housing, transit infrastructure and tax system has been haunted by the region’s fragmented governance.

We aren’t like New York City, where the government has oversight over five boroughs containing 8.4 million people.

For the 7 million people of the San Francisco Bay Area, it’s every city and county for themselves. While there is a council of city governments called the Association of Bay Area Governments that was started in 1961, it’s not sufficiently powerful.

That means NIMBY-ists in every city try and shove the housing issue onto someone else.

That means it’s a race-to-the-bottom on business taxes.

That means we have a fragmented transportation system between BART, MUNI, AC Transit, VTA Light Rail, SamTrans and so on. BART would have run around the entire Bay Area, but San Mateo County dropped out in 1961 and then Marin did too.

Not only is transportation down the peninsula fragmented between all of these different systems, the suburbs have also blocked many denser housing developments along the Caltrain stations that would have supported workforces for companies like Google and Facebook.

.

20) This seems overwhelming. Why doesn’t Google just move to Detroit?

20) This seems overwhelming. Why doesn’t Google just move to Detroit?

Actually, this is happening. Just not in Detroit. Yet.

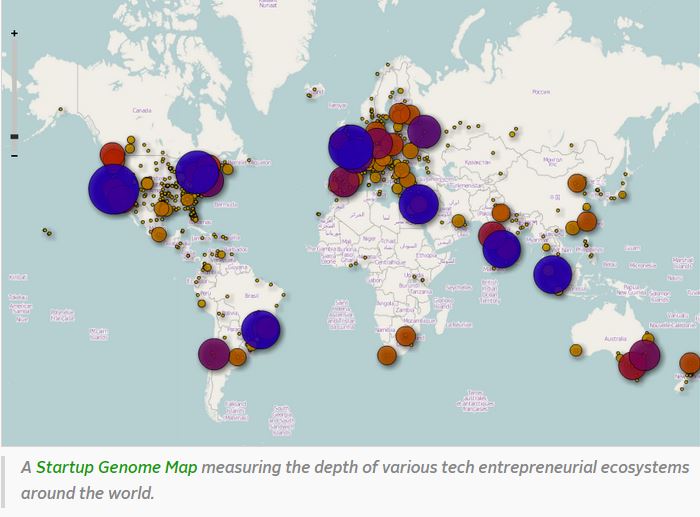

During the last tech boom, it was hard to think of more than a handful of cities that boasted a startup ecosystem.

Today, there are many. The high cost of living in the Bay Area is the rest of the world’s gain. …

While Silicon Valley certainly isn’t in peril, its continued resilience depends on whether it can keep attracting the best talent and new ideas from everywhere.

.

21) We’re fucked.

No, we’re not fucked. If you’ve actually read this far, you know why we’re here.

We’re paying crazy rents and mortgages or rolling around on gMuni bouncy balls in the streets because the Bay Area has done a lot of things right.

I know that the Brookings study showing that San Francisco had the largest increases in income inequality in the country is distressing.

But do you know what else is true?

San Francisco and San Jose have the highest levels of income mobility in the country. Harvard and Berkeley economists Raj Chetty, Nathaniel Hendren, Patrick Kline and Emmanuel Saez examined federal income tax records for 40 million children and their parents between 1996 and 2012.

They found that children in San Jose and San Francisco had the highest chances of moving from the bottom income quintile to the top quintile out of all major metropolitan areas in the United States.

There are the absurd stories, like that of WhatsApp founder Jan Koum, who went from food stamps to selling a messaging app to Facebook for $19 billion.

Then there are the more realistic ones, like that of my mother, who moved to the Bay Area in the late 1970s as a Vietnamese refugee. Because my grandparents were too old to work and they couldn’t speak English, my mother and her five sisters pooled together their earnings to collectively buy a home in San Jose all while in their mid-twenties. They then parlayed the equity from that home into buying homes of their own when they were ready to start families.

We have to remember that cities are unequal because the opportunities they provide attract both the very rich and the very poor.

San Francisco’s extreme juxtapositions of wealth and poverty exist because the city is both an extremely desirable place to live and it maintains protections for residents through programs like rent control and $165 million a year in spending on homelessness.

The gleaming, onyx NEMA towers exist side-by-side with homelessness because San Francisco created the Mid-Market program to lure companies like Twitter and the single-room-occupancy hotels and non-profits that house and feed the city’s poorest residents have been politically protected in the Tenderloin for decades.

Both the tech industry and San Francisco have delicate ecologies that have taken decades to cultivate. As they become more intertwined, the political winds of the city are shifting. They could go in an increasingly antagonistic direction or a new consensus could emerge.

What will it be?

Tech workers: It’s not as easy as just building up. This battle has been raging on since the sand dunes of the Sunset district were flattened for single-family homes in the 1950s.

Try to understand where others are coming from. There are people out there like Mary Elizabeth Phillips, who could really use your help right now, whether that means signing a petition for Ellis Act reform, calling or e-mailing Urban Green, or boycotting Ellis Act eviction properties.

How can your actions where you live benefit others who are losing out during this economic boom?

How will you participate in your community? Will it be through charity? Through volunteership? Through taxes?

Are you willing to fight the political battles and form the alliances necessary to create housing for tech workers and teachers alike? You need to vote, to show the city government that there is political will for development or else the old, anti-growth regime will keep dictating preservationist policies that turn housing into a zero-sum game.

Companies like Gap, Wells Fargo, Levi Strauss & Co. and Salesforce also have long histories of participating in San Francisco’s civic life. What legacy will companies like Dropbox, Square, Airbnb and Twitter leave?

Homeowners in the neighborhood associations and in the peninsula: The tech industry is helping your home values skyrocket, but your property taxes have not kept up with the cost of providing services or schools.

Stop sitting in the background while the city’s workers, the poor, the elderly and its young duke out in this ugly charade.

While there are some tech workers who do strike it rich, most just have salaries and would love to raise families in the Bay Area just as you did when you came here years ago.

The Bay Area risks becoming a victim of its own success if it can’t make more room. At this point, blocking individual housing developments to protect your views is tantamount to generational theft.

Activists: Invoking CEQA clauses to stall the city’s tech shuttle program through an environmental impact review so that 1,400 of 4,000 tech bus riders may or may not decide to move slightly south is not a game-changing way to address housing affordability in San Francisco.

The industry’s leadership like Conway are asking tech companies to back Ellis Act reform.

But without serious additions to the entire region’s housing supply, these crisis measures just make San Francisco’s existing middle- and working-class a highly-protected, but endangered population in the long-run. With such limited rental stock available on the market at any time, what kind of person can afford to move here today when the city’s median rent is $3,350?

For the more extreme groups, you cannot logically fight both development and displacement. The real estate speculation running through the city right now is just as much a bet on political paralysis in the face of a long-term housing shortage as it is on San Francisco’s desirability as a place to live.

Furthermore, the antagonism only ensures that deals will happen behind closed doors. The unfortunate path of least resistance for most tech companies will be to just pay their workers more, instead of engaging in regional politics. That is a loss for everyone.

For the more pragmatic groups, the tech community could easily be persuaded to support inclusionary housing, provided the numbers still work out profitably for developers and that lots more overall housing units gets built. The same goes for Trinity-like projects.

In conclusion: The crisis we’re seeing is the result of decades of choices, and while the tech industry is a sexy, attention-grabbing target, it cannot shoulder blame for this alone.

Unless a new direction emerges, this will keep getting worse until the next economic crash, and then it will re-surface again eight years later. Or it will keep spilling over into Oakland, which is a whole other Pandora’s box of gentrification issues.

The high housing costs aren’t healthy for the city, nor are they healthy for the industry. Both thrive on a constant flow of ideas and people.

So while Google may not be opening a giant office in Detroit anytime soon, the people of Detroit and the Midwest are coming here. …

Many of the people who come here will stay, and make vital contributions for decades through their work, their taxes and their charitable contributions. Some will come for awhile and then go back and invigorate entrepreneurial ecosystems back home. This circulation of creative talent is crucial not only for the Bay Area, but for the rest of the United States.

I would not want to deny anyone — rich or poor — the chance to transform or be transformed by this place..

It’s interesting to compare SF and Vancouver, as there are similarities between the cities, but also significant differences. In both cities their different situations still result in housing which is expensive and contentious.

In San Francisco there is a rental crisis with absurdly expensive rents (seemingly 2.5-3x more expensive than here) whereas in Vancouver rent has risen, but doesn’t seem as brutally expensive for the local populace. This difference seems likely to be due to SF’s lack of development compared to Vancouver, where there’s always cranes on the horizon.

The other driver of high rents could be very well paid tech workers. In SF incomes are high, whereas Vancouver is relatively poor, and has average incomes below many Canadian cities.

In both cities the price of a detached home will easily rise above one million. In SF, where a Silicon Valley job would easily come with a six figure salary, this does not seem too unreasonable, whereas Vancouver’s home prices seem a bit detached from the reality of Vancouver incomes. SF seems like the more ‘normal’ market of the two.

Considering these two cities next to one another, I think gives some weight to argument that Vancouver’s housing prices are in a bubble and possibly fueled by outside property speculation.

Don’t forget San Francisco is part of a Metro Population of 8.6 million (2014 est.) versus 2.5 million (2014 est.) plus there are 200,000 more people living within the city limits of SF. These factors would put large demand on Real Estate and Rents

The discussion is always about fitting more people into existing cities. Once upon a time we were actually capable of building new cities. San Francisco is not the problem, the problem is everywhere else that could be San Francisco, but isn’t. See earlier posts on this blog about the car dependent sprawl in the Bay Area. Vancouver is probably doing better on this front than most places (thanks to policy and also thanks to having so many municipalities in the Vancouver area) but there’s still a lot of room for improvement.

Vancouver 2010/2011 Census Data:

Median Monthly Rent: http://www.mountainmath.ca/census?layer=5

Potion of rental households paying more than 30% of household income on shelter: http://www.mountainmath.ca/census?layer=18

Percentage of rentals that are subsidized:

http://www.mountainmath.ca/census?layer=16

Owned vs Rented:

http://www.mountainmath.ca/census?layer=6