A report in Better! City & Towns on Richard Florida’s presentation to the Congress for the New Urbanism quoted him thus:

One of the false statements is that density and skyscrapers are the key ingredients to urban vitality and innovation. “This rush to density, this idea that density creates economic growth,” is wrong, he said. “It’s the creation of real, walkable urban environments that stir the human spirit. Skyscraper communities are vertical suburbs, where it is lonely at the top. The kind of density we want is a ‘Jane Jacobs density’.”

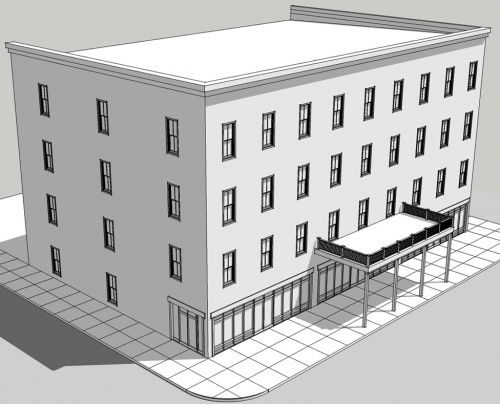

So what is Jane Jacobs-style density? I expect most people think it looks like this (Park Slope, Brooklyn):

.

What she actually said in Death and Life of Great American Cities (pp.208-212) was this:

What are proper densities for city dwellings? … Proper city dwelling densities are a matter of performance … Densities are too low, or too high, when they frustrate city diversity instead of abetting it …

Very low densities, six dwellings or fewer to the net acre, can make out well in suburbs … Between ten and twenty dwellings to the acre yields a kind of semisuburb …

However densities of this kind ringing a city are a bad long-term bet, designed to become a grey area. …

And so, between the point where semisuburban character and function are lost, and the point at which lively diversity and public life can arise, lies a range of big-city densities that I shall call “in-between” densities. They are fit neither for suburban life nor for city life. They are fit, generally, for nothing but trouble …

I should judge that numerically the escape from “in-between” densities probably lies somewhere around the figure of 100 dwellings to an acre, under circumstances most congenial in all other respects to producing diversity.

As a general rule, I think 100 dwellings per acre will be found to be too low.

So what does 100 dwelling units per acre (DUA) really mean?

Well, here’s one place to start – at Better! Cities& Towns: The Dreaded Density Issue by Susan Henderson. But even her comparative images don’t get that high.

36 DUA

Our source is Andy Coupland:

The Olympic Village/Village (right)

on False Creek is 1104 units on about 10.6 acreas of land parcels – so 103/acre.

West End (below) is 318 acres of land parcels, and has 32,750 dwellings so 103/acre.

You pays your money and you chooses your form!.

But beware using dwellings as a measure of density – Olympic Village dwelling average size is 1,117 sq ft; West End is only 772. Very different population density is therefore likely from identical DUA.

UPDATE: Urban densification: a panacea or an apocalypse – another point of view from the North Shore.

Imagine what the density of the olymipc village could have been if they had chosen to build more affordable, middle-class units rather than luxury condos that no one wanted to buy. It would have been a much more vibrant, more diverse neighbourhood, and better for the city. Too bad that boat’s already sailed.

Don’t forget that the Village is only a small part of South East False Creek. On the city block to the north, Wall Centre False Creek and The Residences at West will have over 1,000 units on 3.4 acres of land – 300 dua. There’s retail and a theatre space on that block as well. The average unit site is around 710 sq ft, much closer to the West End, but that includes a range of sizes from studio to family townhouses. http://changingcitybook.com/ has images of both projects – Wall Centre’s construction is really moving fast these days.

About a decade after the 1961 publication of The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jane Jacobs began to rethink her conclusions in regard to density—not the general principle that sufficient but uncrowded population density is needed to produce vibrant city life—but in regard to her estimates of dwelling units per acre (DUA).

This revision was in part the result of moving to Toronto’s Annex in 1968. The Annex is a large district, bounded by Bloor Street on the south, Dupont (north), Bathurst Street (west) and Avenue Road (east). It was developed in the early 20th century as a streetcar suburb, with detached and semi-detached brick houses, mostly three storeys in height. Over time, a few low-rise apartment buildings were added, and starting in the late 1960s, several moderate highrises (ca 15-storeys) with large setbacks, mostly on or around Spadina Road. Many of the old houses have a secondary suite, or are entirely apartments (think Kitsilano). Starting in the 1970s, due to Jane’s influence, low rise non-destructive infill was added to several large lots and to replace homes that had been demolished for cut-and-cover construction of the Bloor subway (when the Spadina Line was tunneled, a heritage house was repurposed to serve as a station).

I don’t know what the density of the Annex was, or is at present, but I am sure it is far less than 100 DUA. Yet Jane saw that it supports a vibrant, walkable community, with a wide range of shops and services, as well as rapid transit. While its moderate density would not be appropriate for many downtown areas, the Annex, and many similar neighbourhoods in Toronto, Vancouver (e.g. Grandview, Kits, Mount Pleasant), and other cities, are by no means destined to become “grey areas” or “nothing but trouble.” In fact, if consistent with other key principles imparted in The Death and Life (e.g. small blocks, mixed uses, aged buildings) they can complement the more heavily built up core areas in a variety of ways. For example, downtown residents enjoy visiting low-density Riley Park (where I live, and of which Jane thought highly), not only for the second hand stores, antique shops, galleries and cafes, but the neighbourhood’s “small town” feel.

In several discussions I had with Jane, ca 2000, she allowed that in 1960 she had overestimated the densities needed for city districts to be successful. She asserted that density is only one of several key attributes, which in various permutations affect the economic and social functioning of city neighbourhoods, and over-reliance on rules of thumb (e.g. 100 DUA) is problematic in planning. While neighbourhoods need diversity in various forms, diversity between neighbourhoods—including differences in character, uses and density—help create better cities. Although in 1960 she had admittedly overestimated the densities needed for successful city neighbourhoods, in the same chapter—“The need for concentration”—from which Gordon Price quotes, she included this caveat:

“The ‘in-between’ densities extend upward to the point, by definition, at which genuine city life can start flourishing and its constructive forces go to work. This point varies. It varies in different cities, and it varies within the same city depending on how much help the dwellings are getting from other primary uses, and from users attracted to liveliness or uniqueness from outside the district.”

Regarding the Annex, I think the major factor is that it’s basically right next to downtown. With the office and residential towers at Bloor and Yonge, the mostly mid-rise U of T, two subway lines, ROM, hotels… there’s a lot of density nearby that the Annex can draw in pedestrian traffic from, and a lot that can bring in visitors from other parts of the city. The density of many of these adjacent places is similar or even higher than the 100 DUA neighbourhoods like Greenwich Village. It probably helps that there’s little retail within the U of T campus that’s adjacent to the Annex.

As for the two subways, at the time they were built, The Annex was probably similar to many other neighbourhoods in Toronto that don’t even have a single subway much less two. You’re probably more familiar with the history, but wasn’t The Annex just lucky to be in the right location rather than anything specific to the Annex being the reason it got two subway lines? I think Bloor was chosen for the E-W subway to be close to the geographic centre of the city which was expanding North with the development in North York and beyond, and the University-Spadina line was meant to serve the western part of downtown with the extension north of Bloor intended to relieve congestion on the Yonge line and/or on roads (since the Spadina expressway was cancelled) from commuters heading to downtown?

(also about 50% of housing units in the Annex are in buildings of 5 storeys or more, so even if some of them don’t meet the street very well and might not attract that much pedestrian traffic, I suspect they still generate a fair bit of pedestrian traffic).

In Summary: I think The Annex benefits significantly from its central location, as well as the ability to bring in more non-residents (hotels, students, office workers) than it “sends out” due to factors specific to its location. Build a neighbourhood that’s a replica of The Annex in the middle of Scarborough and I don’t think it would have worked as well.

That being said, Toronto and Canada in general didn’t have as severe social and political issues as the US, so places like the Italian/Portuguese/Jamaican neighbourhoods around St Clair West or Eglinton West, despite having many similarities to American “grey belt” neighbourhoods, managed to avoid serious decline. Even the housing projects of Toronto seem to be significantly safer than American ghettos (at least based on homicide rates).

And regarding using DUA instead of FSI/FAR or population per acre, I think you have to be careful. You don’t want to resort to making smaller and smaller units as the main way to increase density. When there’s an oversupply of large units, building small ones make sense. However, within the GTA, some of the highest densities in terms of people per sf of living space are in certain parts of Brampton that have relatively large single family homes. That’s because of large household sizes, often with extended families living together. Many neighbourhoods there have household sizes of 4 or more, compared to 2.7 I think for the GTA average and 1.6-1.7 for The Annex. When you think about it, it makes sense, large households can share kitchens, living rooms, dining rooms, even bathrooms to a certain extent. I think that the only parts of the GTA to rival Brampton’s denser SFH areas – aside from a few similar SFH neighbourhoods in other suburbs, are the tower-in-the-park communities like Flemingdon Park and Crescent Town.

Larger units are important for families, and they should be relatively affordable if you want to have more than Lawrence Park type upper class families. Larger units can also make sense for room-mate arrangements or boarding houses. I think it might be better to look at FSI/FAR and allow the building owners to configure that space however they want, with whatever household types. I’m not sure what The Annex was like before, but today, with the combination of small units and relatively high prices, it seems to be mostly bachelors, students and childless couples, there isn’t a whole lot of children.

So what is Jane Jacobs-style density? I expect most people think it looks like this (Park Slope, Brooklyn)

By this standard, I’m not ‘most people’. I whole-heartedly agree with Ned’s presentation of his mother’s point. The Brooklyn building is a tenement (apartment) building. My less than thorough understanding of this building type (also found in the Back Bay of Boston), is that it is post-Civil War, and replaced row houses.

When talking about net density, it is important to point out that the difference between the row house and the apartment building is 15%. That is the amount of floor area typically given over to hallways, stairs and elevators in apartment buildings. Areas that do not exist in houses that have the door opening directly on the street, front door yards, rear yards and roof decks. So, 100 units per acre apartments or tenements translate as 85 u/ac row houses. That is only 10% above what we can achieve here in Vancouver with 4-storey houses on lots that also have 20-foot rear lanes, and 66-foot rights-of-way. In Greenwich Vilalge, the typical street is just 50-foot wide, fronting blocks that typically do not have a rear lane. Small differences, I know. But important issues when the pencil is sharpened in a very, very competitive market place.

A straight-lline comparison of ‘Jane Jacobs’ density is just too simplistic. We need to take into account other factors including neighbourhood footprint, streets & squares, the mix of building types, the plat or urban grid, social mixing, and the economics or financing of both public and private construction.

A better place to focus our attention is on Ned’s observation about the role of diversity between neighbourhoods in building better cities:

I see this in Ottawa where I live in that we have three more or less contiguous neighbourhoods – a high rise dense area, moving into a west-end lite mixture of older apartment buildings, houses and 15 – 20 story apartments, then a streetcar suburb. Each neighbourhood has its own character, but they all complement each other.

Lewis – where can I see townhouses at 85 dwellings per acre? The Grand on Oak that was completed in 2009 is almost exactly an acre in size, and that has 31 dwellings. The two townhouse projects that Mosaic built behind the Oakridge Mall on Tisdall Street are 36 per acre and the townhouses that replaced part of Champlain Mall seem to be at most 40 to the acre. The highest density I can find.is a project called Weston Walk on Ash Street, completed last year. It has 53 units on just over an acre, so it gets to 51 per acre. The interesting thing about this project is that it has 35 houses, and 18 of them have lock-off suites that can either be used as part of the main house, or as a rental suite. They’re seem popular – the two that are currently for sale are asking $1.3m without a suite and $1.5m for the one that does.

Jane Jacobs’ main point was that planning has been based on assumptions of what in theory should work rather than in practice how things actually work. She challenged these theories and advocated looking outside the box of assumptions to what really happens in cities. Planning is much more than a numbers game since there are so many variables depending on the context, size of units, etc. There is no magic number of units per acre.

Many of Jane Jacobs’ observations have been taken out of context and applied into planning theory. This has been used to support “towers in the park” and other forms of development that she railed against, with a podium of “eyes on the street” townhouses to justify them. Although tower and podium development form may work downtown, it is not the holy grail of urbanism.

She was opposed to existing neighbourhoods being demolished and replaced by major new planning projects, rather than evolution using existing buildings of various ages and infill of human scale. Cities built or designed before WW1 were used as her model, before vehicles and when they used street cars. Short streets with lanes, smaller lots (street frontage) where each lot is owned by individuals rather than large land owners. Most of the City of Vancouver was originally built on this model.

In “Chapter 10: The need for aged buildings” Jane Jacobs states “The district must mingle buildings that vary in age and condition, including a good proportion of old ones.” This was to ensure that there were sufficient numbers of older depreciated buildings, “fixer-uppers” that can be both affordable accommodation and for businesses.

Therefore, density should vary from neighbourhood to neighbourhood allowing for diversity, stability and community character. There is no specific preferred density for all city neighbourhoods to be the same.

Further to Andy’s facts noted above – thanks for facts rather than notions!- if we take the prevailing C2 mixed-use zones along our arterials at the permitted 2.5 FSR, roughly about 1.75 to 2.0 of that is located on the 3 residential floors above the retail floor. At an average of (smallish) 1000gsf per unit, we get about 75-85 units per acre. Smaller units generate more units if not people per acre, while larger average unit sizes do the reverse.

In comparison, our purely multi-family residential areas at 4 storeys having an outright density of 1.45FSR generates no more than 60-65 units per acre, depending on unit size, of course. It is around this density that 3 storey stacked townhouses at 1.2 FSR reaches a similar theoretical upper limit of 60-65 upa. In reality, more likely in the roughly 50upa range, as Andy Coupland rightly notes.

I believe that the Florida reference pertains to rush to building highrises.

Note that Susan Henderson’s figure for the apartment building is based on 1.5 parking spaces per household, which is far higher than is needed in any transit or bike-oriented neighborhood. Here in Portland, where parking minimums were removed several years ago in neighborhoods with frequent transit, most new apartment buildings have around 0.5 parking spaces per unit, and several have been built with zero parking. Once parking is not required, density can be increased without requiring any additional height.

Zev – is the added height due to parking structures at or above grade? Here in Vancouver, if not in places with high water tables or flood plains like richmond and Coquitlam Town Centre, we generally don’t permit parking structures to be above grade grade, therefore there generally aren’t any additional height impacts.

Reduced parking ratios in TOD nodes and corridors make a lot of sense, otherwise. A signficant determinant of this from a policy point of view is whether capital cost savings have been passed on to the buyer or renter. I’d like to know if this kind of saving has been borne out in Portland.